|

|||

| Serge Lemoine :

From Puvis de Chavannes to Matisse and Picasso. Palazzo Grassi, Venice, 2002.

There is an artist whose influence on the history of art in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries was of great consequence. Throughout Europe and in America. His name has not fallen into oblivion. Yet in our day it no longer reflects that importance nor that status, since it is neither Monet nor Van Gogh, nor Rodin nor even Cézanne, nor any other name the public is so fond of, shown everywhere, reaching astronomical prices in auctions, appearing in books and on the covers of high-circulation magazines. It is that of the French painter, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, who lived from 1824 to 1898.

Today the history of modern art, to thus define twentieth-century art and looking at it from our contemporary vantage point, is told in elementary, linear terms: we all know it. It starts with Impressionism, where Manet, Monet, Renoir, Degas are indistinctly associated, followed by Post-Impressionism with Seurat, Van Gogh, Gauguin and Cézanne; it continues with Fauvism and Matisse, through Picasso and Cubism, reaching abstraction with Kandinsky. Surrealism, which comes later, is to be added although it is difficult to place it in that sequence. The rest proceeds accordingly. Nowadays this interpretation is accepted—and has been for some time—by the majority of historians, critics, and the public whose tastes and values it conditions, and even by most artists. Yet such a historical description, in which Impressionism is considered the source of modern art, presents, and has always presented, a great number of issues that remain unexplained and inexplicable, as soon as it is examined without preconceptions, like the transition from Monet to Cubism through Cézanne, or from Cubism to abstraction, when the art of Mondrian and Malévich, not to mention Kandinsky and Kupka, has so many spiritualist implications. To be more explicit, can Picasso's works of the Blue and Pink Periods be explained in terms of Toulouse-Lautrec, Steinlen, or even Gauguin, as is done? What relationship with prior works is to be found in the Matisse oil Luxe, calme et volupte with its Divisionist technique, Bonheur de vivre with its vivid, rapid and undulating touches of color, the two versions of Luxe in which line suddenly prevails at the expense of color, and lastly, Music and Dance with their bright contrasting uniform hues? Further along in the twentieth century, what is one to think of Picasso's subjects during his so-called "Neoclassical" or "Ingresque" period, and of their treatment? Just where do they come from, those frieze-like compositions with their singular colors, parallel bands of earth, sea and sky, and themes that are so particular, which the artist would continue to use up to his "monstruous" figures of the 1930s? Just why did Matisse remain faithful to the theme of dance when he executed Dr. Barnes's commission, and why did he treat the lunettes of the building with those forms, those flat, uniform colors? During the last part of the nineteenth century and around 1900, why does one run into so many painters in the world who have nothing in common with Impressionism, and who no longer belong to the category of academic and eclectic art commonly qualified as "art pompier"? Every one of these artists, including a fair number of sculptors, display a great unity of style and content in their production that causes them to be grouped today under the denomination of Symbolism, a trend to which even Gauguin, with his philosophical subjects, belongs. A complete opposite, Seurat: but nor do his compositions reveal any reminiscences of Impressionism. These few questions, raised helter-skelter among innumerable other ones, cannot be answered when they are considered from the point of view of Monet's, or even Cézanne's posterity. They might confirm the theory of the "break," a break between the art of the past and that of the twentieth century, so dear to those spirits that reject the latter as a whole and sigh for "bygone craftsmanship." Is it feasible today to challenge that univocal history, that has become tradition, some might say vulgate, that appears to be so unsatisfactory with respect to the wealth and complexity of its manifestations? One must leave aside ready-made formulas and prejudices, and go back to history itself to concentrate on the facts and their manifestations, and then examine what has taken place since the beginning of modern art, rather than the reverse, that is, start with what is known and accepted today and go back in time. Such a reappraisal enables us to understand that as early as 1865 there was a painter who was not part of the fashionable trends of fossilized tradition, nor an Impressionist, Realist, or academic, and who contributed a new language and powerful, simple concepts as well as an artistic ideal. These concepts were so thoroughly appreciated by his contemporaries, the next generations, and the public less than twenty years later, that they exerted a profound influence all over the world and lasted until late in the following century. That painter, as we already claimed, is Puvis de Chavannes.

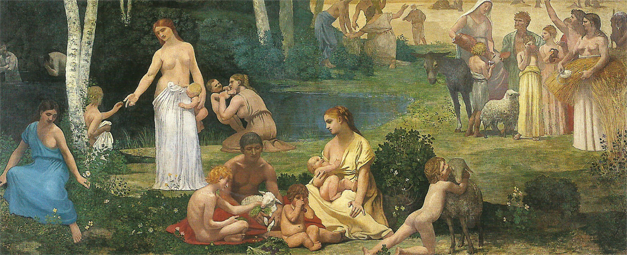

His art—expressed in monumental decorative schemes covering huge surfaces that were integrated into the architecture, and in easel paintings of all sizes, some of large format—has two main components: a subject and a form. The latter consists of simplified pictorial elements, that can go as far as schematization, a concise draftsmanship, an economy of muted shades, a decided flatness at the expense of illusionistic depth. As for his technique, it is unaffected and occasionally crude, even in the small formats. The content is based on allegory, and shows a preference for simple themes that are displayed without narration or psychology, but which emanate a poetry, that may be elegiac, gloomy or even tragic. The paintings Hope (1872), Young Women by the Sea (1879), and Dream (1883), with their directly approached subject, their silence and their utterly timeless appearance, are true pictorial poems, that are achieved through their rarefied composition, the inter-locking of the forms and the accurate appropriateness of their colors, while the two versions of The Prodigal Son. (1879), and even more so The Poor Fisherman (1881), with its utter bareness, express dereliction and poverty, without literary or picturesque effects. As for the large decorations, those of the Musée de Picardie in Amiens in their two stages (1861-65 and 1880-82), and in particular the one titled Ludus pro Patria; the composition Pleasant Land painted in 1882 for Léon Bonnat's residence in Paris; the monumental paintings of the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon (1884-86) and especially The Sacred Wood Dear to the Arts and Muses; the two cycles dedicated to the story of Saint Geneviève in the Panthéon in Paris (1874-78 and 1893-98), their scope, ambition, science and simplicity reveal a perfect balance between subject and the form in which it is expressed, painting and space, poetic invention and the constraints of the wall. That art of composing with such ease, illustrating with such clarity, simplifying everything including the brushstroke, getting to the essence without overlooking detail, creating lasting images without being narrative, explains Puvis de Chavannes's singular position in his day. As soon as he found his own way in the 1860s, his style had nothing to do with that of the different figures of the art of the Second Empire and the Third Republic, neither Cabanel nor Baudry, neither Bonnat nor Meissonnier, who triumphed in the Salon where he too exhibited. He had nothing in common with the art of the Impressionists and the Salon des Refuses, neither with Manet, nor Pissarro nor Monet, there was no realistic interpretation of landscape and atmosphere, nor any fondness for still life, nor attraction to the ephemeral and the changing, or any recording of the anecdote nor representation of the everyday commonplace. Only Degas, with his rigor and his daring, shows true affinities with Puvis de Chavannes: at the beginning of their careers, did they not both refer to the same model, Ingres, along with fourteenth-century mural art? Puvis de Chavannes's monumental decorative schemes, paintings, and drawings, which betoken the most accomplished art, the most unrelated to the times yet the most directly connected to the grand tradition, enable us to grasp the influence he had on his contemporaries and the next generations, whereas the Impressionists's art had no effect, except that of stirring healthy reactions against it; and that of Degas, which was too particular, had no noticeable posterity. Puvis de Chavannes's position was comparable but superior to that of Jean-Francois Millet several years earlier, who also left his mark for the same reasons—the sense of synthesis, the reduction to types, the expression of timelessness and creation of strong, unforgettable images—on artists like Van Gogh, Seurat, Gauguin, Segantini and countless other painters, who were to emulate, occasionally at the same time, the works of one or the other of these masters. The authority Puvis de Chavannes wielded finds a good illustration in the banquet offered in his honor in 1889 in Paris. Planned and presided over by Auguste Rodin, it gathered 550 persons, painters, sculptors, poets, writers, critics, composers, politicians, civil servants, art lovers, happy to show him their admiration. In his lifetime, entire generations of artists, in particular from Scandinavia, Germany, Switzerland, America, flocked to the French capital, choosing his art as their model. Puvis de Chavannes at the time played the same role as David around 1800, one that after him would be Mondrian's, and his fame contributed to consolidate Paris as the capital of art. He died in 1898, universally admired.

His fame did not prevent him from falling into disfavor. After World War I, his name began to be forgotten by public opinion, historians, critics and artists, despite the fact that several books appeared glorifying his art, including the one by Camille Mauclair. And yet at the very same time, the reputations of a few of his most brilliant disciples, Bonnard and Vuillard, Matisse and Picasso, were spreading, and young, more or less marginal painters like Balthus, were in turn discovering him. Neglect and then oblivion soon led to incomprehension and even a complete misinterpretation of his work. It is possible to see the reasons, yet not easy to explain them without appearing to over-simplify. The first aspect has to do with Puvis de Chavannes's preferred means of expression, monumental painting, that gradually became unfashionable owing to the transformation of architecture combined with the evolution of taste. The decorative scheme of the Palais de Chaillot, built in Paris in 1937, was similar to those of the same period in official buildings in Italy, Germany and the USSR, and is to be considered one of the last expressions of a way of conceiving the integration of the arts, at a time when Rietveld's Schroder house in Utrecht, Gropius's Bauhaus in Dessau, Mies van der Rohe's German pavilion in Barcelona, and Le Corbusier's villa Stein-de Monzie in Garches had already revolutionized the art of building. There is another reason of a different order that has as much to do with the field of sensibility as with the evolution of mentalities: we can discern it in the growing taste for a kind of painting that is immediately accessible and has nothing to prove, Picasso's Guernica and certain Surrealist paintings illustrating exactly the opposite. In other words, the triumph of Impressionism, which appeals to immediate sensation, whereas "old" painting is held to be difficult or even grim. Deeply-thought out composition is cast aside for improvised painting, which is expressed by slapdash craftsmanship or, on the contrary, ploddingly overdone as in Van Gogh. The final result: small and medium-size formats became popular, art in the first half of the twentieth century having entirely, barring exceptions, shifted its ambition: easel painting, faster done, cheaper, easy to move, showable and sellable, lastingly won out over "great painting." All these features, revealing essential changes in mentalities and habits, ended up by prevailing as the sole criteria of modernism: they would lead to a series of misunderstandings, beginning with the one whereby Puvis de Chavannes's art, despite the evidence, would become identified with "art pompier." That misconception reached a climax in Paris in 1968 when his painting at the Sorbonne was ridiculed at the time the University of Paris was occupied by demonstrators, several of whom—true barbarians—even suggested destroying it. That state of mind was also expressed when Surrealism had finally won its ground and explaining it and seeking out its sources had become necessary, just when Symbolism was beginning to surface again. It was then that the figure of Gustave Moreau, whose work was so literary yet of an inferior pictorial quality, was rehabilitated, while Puvis de Chavannes was even more obfuscated and misunderstood. Thus, during the second half of the twentieth century and in step with Marcel Duchamp's rising importance, whether it be legitimate or based on mistaken beliefs, the art of Puvis de Chavannes was forgotten. Beginning in the 1970s, a series of exhibitions and books would undertake a reappraisal, first of all of Symbolism, a movement that had been entirely neglected because of the exclusive taste for Impressionism. In 1976, the exhibition Le Symbolisme en Europe was therefore able to draw up a first inventory of that singular art, in which Puvis de. Chavannes was just one name among many others. The following year, the book Journal du Symbolisme by Robert L. Delevoy sought to provide explanations and interpret the complexity of trends within that movement: Puvis de Chavannes was not overlooked, however, he was presented therein as less important than Moreau or the Pré-Raphaelite artists. In 1995, the enthralling Montreal exhibition Paradis perdus: I'Europe symboliste considered the events of that period from an iconographic point of view, striving to present it in a literary manner and failing to appreciate the role Puvis de Chavannes had played. Again in 1999, the exhibition at the Musee d'lxelles Les Peintres de L'âme. Le Symbolisme idéaliste en France mentioned the existence of Puvis de Chavannes without pointing out his past supremacy. Finally the exhibition at the Royal Academy of London titled 1900 Art at the Crossroads, organized for the year 2000, simply offered an overview devoid of main lines of direction or hierarchy, and Puvis de Chavannes, who had died in 1898, was missing, whereas he should have been one of the leading references of the period. Last of all and in another register, one will be amused to note, since it is a perfect illustration of that same frame of mind, Georges Banu's work L'Homme de dos, peinture et théâtre, which came out in 2000 and was hailed by the critics, where Puvis de Chavannes's name was not even mentioned.

Rehabilitation of Puvis de Chavannes, as well as emphasis on the role he played in his day and the influence he exerted later on, came from across the Atlantic. By 1945, the American art historian Robert Goldwater, inspired, he claimed, by a suggestion from Alfred H. Barr himself, had already published an article on the subject. Then in 1975, Richard J. Wat-tenmaker, at the time chief curator of the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, held a first exhibition on Puvis de Chavannes in which he proved, with deep insight and a perfect grasp of the importance of the fact, how great his influence had been. At the time counter to the mainstream, his splendid undertaking remained limited and unique, despite Hilton Kramer's favorable review in the New York Times which, to tell the truth, appeared shortly before the show closed. The first retrospective devoted to Puvis de Chavannes was organized in Paris by Jacques Foucart and Louise d'Argencourt, before traveling to Ottawa. Despite its quality and scope, reception was poor and did not alter the opinion on the artist, nor did the very erudite catalog of Puvis de Chavannes's drawings conserved at the Musée du Petit Palais in Paris, which was published in 1979 by Marie-Christine Boucher, and which did, however, confirm the artist's importance as a draftsman. There followed afterthoughts, various mentions, a few specifications, the ones by Pierre Vaisse for instance, who underlined in 1983 the connection between the art of Ferdinand Hodler and that of Puvis de Chavannes, while Francoise Cachin in turn pointed out Gauguin's ties with Puvis in her book on the Tahiti painter published in 1988. Pierre Schneider, in his 1984 milestone book on Matisse, stressed what the author of Dance owed to Puvis. And Paul-Louis Mathieu, who examined the period from an historical point of view in La Génération symboliste of 1990, underscored the figure of Puvis de Chavannes. Anne Distel and especially Michael F. Zimmermann, in their respective studies of Seurat's work published in 1991, showed to what degree the art of the Lyon master had nurtured the inventor of Pointillism. Kenneth E. Silver, in his 1991 book titled Vers le retour à l'ordre was fully aware that Picasso's sources after World War I were to be sought in Puvis de Chavannes, as Anne Eggum did in 1992 for Edvard Munch in her biography of the artist, appearing in the catalog Munch et la France. In 1995, Pierre Daix in his Dictionnaire Picasso referred to Puvis as the source of the painter's Blue and Pink Periods. The exhibition Pierre Puvis de Chavannes at the Van Gogh Museum of Amsterdam in 1999, curated by Aimee Brown Price, insisted in turn on the importance of Puvis's art, and briefly recalled his influence, by means of several examples. Last of all, in 2000, at the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen, Peter Norgaard Larsen demonstrated Puvis's vital role in that part of Europe, in the exhibition titled Symbolism in Danish and European Painting 1870-1910. However, those events have still not succeeded in revising the overall perception of Puvis de Chavannes's work. Compared to the prestige of the names of Manet, Monet, Van Gogh, and those of Cezanne and Gauguin, the figure of Puvis de Chavannes has not yet been rehabilitated. One only has to see in order to understand. In the 1860s, Puvis de Chavannes's style had evolved in the compositions for the Musée de Picardie in Amiens, where he placed his panels Work and Rest, War and Peace, which were completed by the composition Ave Picardia Nutrix, and which spanned the years 1861 to 1865, plus the two decorations for the Palais Longchamp in Marseille (1867-69). His art, that was to continue to develop over thirty years, would be known, widespread, viewed and discussed, to the point of provoking veritable rejections as well as fervent enthusiasm. And his fame would continue to grow. Concurrently with public commissions for Poitiers, Lyon, Rouen, the Pantheon, the Sorbonne and lastly the Boston Library, one exhibition at the Salon followed another, with the same works being shown more than once. Before being installed in the buildings, the monumental compositions were also exhibited as soon as they were completed, so that the public and artists could see them, in the same way their cartoons and reduced copies were shown later on. The galleries, in particular Durand-Ruel in Paris and New York, showed his work exhaustively on several occasions, and in 1899 after his death, while a tribute to him was held at the Salon d'Automne in 1904. He exhibited alone or in group shows on different occasions in Paris and abroad, in Brussels, Venice, Scandinavia, Germany, Italy, and America. Puvis de Chavannes was known, understood and admired, and his influence was immediately felt.

Early in their careers, Puvis de Chavannes and Degas were quite close, and then they parted ways. But Degas, who collected Puvis's drawings, continued to pay attention to his art and at the end of his life rediscovered some of his friend's solutions in his own works on paper. Odilon Redon was strongly influenced by Puvis, and would retain his chalky, unpolished, hazy backgrounds, his succinct forms, and of course his fondness for the line: his paintings frequently seemed to be enlarged details of Puvis's compositions, like The Prisoner (Cologne, Wallraf-Richartz Museum). Eugène Carriere, who was a friend of Puvis and painted his portrait (Lyon, Musée des Beaux-Arts), did not fail to be influenced by him, his work becoming as flowing and evanescent as Puvis's was firm and composed: the painting The Young Mothers (1906, Paris, Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville) looks like a copy of the central part of The Sacred Wood. When everything was against them, the Impressionist painters, who were nevertheless defended by Puvis, were able to take his example into consideration: In this way, Auguste Renoir's painting The Bathers (1887, Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art), appears more completely Puvisesque in its subject, composition and treatment of forms than Ingresque, as has been said. Even the highly personal Auguste Rodin was deeply indebted to Puvis's art and his treatment of the subject, as we can see in particular in the bearing of the statue The Age of Bronze (1875-77, Paris, Musée Rodin), and in its movement and the accuracy of its contour. Rodin was the one to arrange the banquet given in Puvis's honor for his seventieth birthday, and remained one of his most enthusiastic admirers until the end of his life. Along with France, Germany: Hans von Marees came to Paris at an early age in 1873-74, and deeply impressed by Puvis's compositions, remained loyal to him leaving in turn a decisive legacy to German art.

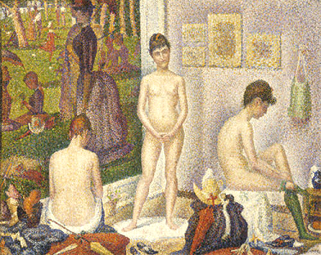

After the generation of artists born in the 1840s came that of the painters customarily called Post-Impressionists—a term that should be discarded today—and that of the Symbolist artists, whom cannot be dissociated from one another: was not Seurat a friend of Aman-Jean? And Gauguin is obviously a Symbolist artist, like many Nabis, who emulated him just as they did Puvis. The Neo-Impressionists were among Puvis's first disciples, the ones who textually borrowed his lesson and even his solutions, transposing them in modern subjects. From the start, Georges Seurat painted a Tribute to Puvis de Chavannes (1883-84, Paris, private collection) in a rough sketch showing The Poor Fisherman placed on an easel outdoors. The trend was set. Bathers at Asnières (1883-84, London, National Gallery), so impressive in its stillness, its pale colors and utter simplification, borrows the tripartite arrangement of Pleasant hand, the rear-view and profile placement of the figures, the play of arabesques Puvis had invented, and which the painting Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-8.5, Chicago, The Art Institute) would carry to its ultimate consequences with its frieze-like composition, stylized figures incorporated into a decor rhythmized by the layout of the trees, its oblong rectangular format, and monumental dimensions. The Models (1886-88, Merion, The Barnes Foundation) flippantly plays with sequences of lines, while the composition of Circus Sideshow (1887-88, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art), radicalizes Puvis's teaching, by emphasizing frontality, lack of depth and the succession of rhythms.

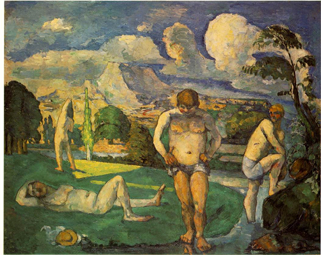

Georges Seurat - The Models,

Circa 1898, Private Collection. Paul Signac, who was Seurat's friend, was to return at a later date to Puvis's conceptions in Women at the Well (1892, Paris, Musée d'Orsay) and several other landscapes (Saint-Tropez The Door, 1896, Bucharest, National Fine Arts Museum of Romania), but his most important work, In the Time of Harmony (1893-95, Montreuil, Hôtel de Ville), looks like a transposition of Pleasant Land. As for Henri Edmond Cross, he seems more literal, but also more stylized as well, Evening Breeze (1893-94, Paris, Musée d'Orsay) appearing to be a thoroughly idealized evocation of Eden. The other Pointillists, Theo Van Rysselberghe and Hippolyte Petitjean, illustrated identical themes that Maximilien Luce pursued in a casual vein up to the 1930s. Along with Seurat, Paul Gauguin is the artist who most closely studied Puvis de Chavannes. When he left for Tahiti in 1891, he took along a reproduction of Hope (nude) by Puvis, that he quoted in particular in one of his paintings, Still Life with "Hope" (1901, private collection). A late starter who had to feel his way, as soon as he moved to Pont-Aven he became Puvis's main disciple and remained so until the end,. He was even more faithful than Seurat, since he retained and developed figuration, directing it toward symbols and philosophical meditation. Still, he was also freer, since he was successful in combining arabesque and color and went further in abstraction, that is, non-realism. Youths Bathing (1888, Hamburg, Kunsthalle) and Young Boys Wrestling (1888, London, private collection) might be literal quotations from motifs of Pleasant Land, whereas the composition of his paintings, the relationship of the figures with the background, the themes illustrated in Ta Matete (1892, Basel, Kunstmuseum), a group of figures; Vairumati (1897, Paris, Musée d'Orsay), an isolated figure; Two Tahitian Women on a Beach (1892, Honolulu, Honolulu Academy of Arts), silhouettes seen in rear view standing out against the horizontal parallels of the landscape; and the humanist and esoterical epitome embodied in Where Do We Come from? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897, Boston, Museum of Fine Arts), in their rendering and their interpretation of Puvis, constitute the highest tribute he could receive. The rear-view or profile figures, the stylized elements of the setting, vegetation and architecture, the animals, horses, pigs, dogs and cows painted so synthetically, the accessories and all the simplified objects, and, finally, the ambition of the subjects to achieve universality denote the many elements Gauguin had been able to perceive and make his own in Puvis de Chavannes's art. And he would influence Emile Bernard, who would look at Puvis on his own, as can be seen in his painting Bathers with Red Cow (1889, Paris, Musée d'Orsay). Vincent Van Gogh deeply admired Puvis, as his letters prove, but to a lesser degree his painting. As for Paul Cézanne, he would borrow frontality from Puvis, which he would employ in his landscapes and his figures, the tripartite arrangement of space—with earth, sea and sky (L'Estaque, View of the Gulf of Marseille, c. 1878-79, Paris, Musée d'Orsay), as has been seen in Pleasant Land and, of course, in the cycle of the Bathers—the vast compositions, incorporating figures, seen standing from the back or in profile, crouching or coming out of the water in rear view in a landscape rhythmized by trees. Pierre Puvis de Chavannes - Summer (detail)

1873 - Orsay Museum, Paris Paul Gauguin - Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?

1897 - Boston, Museum of Fine Arts.

As we know, Seurat, Van Gogh and Cézanne had a decisive influence on the following generations. First of all, that of the Nabi artists that appeared around 1890 and was also involved with Symbolism, which was of the same period, and which shall be discussed later: After all, The Talisman (1888, Paris, Musée d'Orsay) by Paul Sérusier was painted under Gauguin's guidance, and did not Maurice Denis render a Tribute to Cézanne (1900, Paris, Musée d'Orsay) ? Yet, on close examination, it is to Puvis de Chavannes that they owe their art. First and foremost, Maurice Denis, whose admiration was boundless as we see in his Diary. He mulled over, assimilated and developed the ideas contained in Young Women by the Sea and in Sacred Wood: the frieze-like composition, the expression of space, the choice of colors in which muted shades prevail, the forms reduced to the decorative arabesque, which would become the leitmotiv of Art Nouveau and whose early stages can be found in Gauguin; last of all, the expression of rhythm, produced by the position of the figures and their relationship with the trees. Maurice Denis is famed for his definition of painting as "a flat surface covered by colors assembled in a certain order." Yet, paradoxically, the subject plays an essential part in his work, as can be seen both in his contemporaneous and timeless representations, titled Bathers at Perros-Guirec, or else The Muses, The Orchard of the Wise Virgins and Sacred Wood. In his early days, Pierre Bonnard did not fail to emulate inventions from Inter Artes et Naturam, as we can see in his painting The Big Garden (1898, Paris, Musée d'Orsay), even in its horizontal format. Likewise, Edouard Vuillard had perfectly assimilated Puvis's arrangements, that he found in intimist subjects like Green Interior (1891, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art) as well as in the large ensemble of decorative panels based on the theme of Public Gardens (1894, lost). Ker-Xavier Roussel followed suit with his representations of contemporary scenes which he then abandoned for far more literal evocations of antiquity. The other Nabi painters, Paul Sérusier, Jan Verkade, Charles Filiger, Paul Ranson, Pierre Girieud were undoubtedly followers of the Gauguin of Pont-Aven and of Emile Bernard, but they were above all loyal disciples of Puvis de Chavannes, occasionally converting his themes to esoterism, as in Nabi Landscape by Paul Ranson (London, private collection). Within that group, Aristide Maillol's position was special. As a painter first, he was entirely under the sway of Puvis's art, as can be seen in the copy he made in 1887 of The Poor Fisherman (Paris, Musee d'Orsay). He quickly and precociously found his own style within the world of Puvis {The Crown of Flowers [A Meadow Subject], 1889, Copenhagen, Ny-Carlsberg Glyptothek), even drawing his inspiration from Christian Inspiration, the most ignored panel of the stairway of the Musée des Beaux-Arts of Lyon (Portrait of Aunt Lucie, 1892, private collection). When, after 1895, he began practicing sculpture, he invented a world of smooth, full forms, sensuous and idealized, that owes nothing to Rodin and everything, including the use of allegory to Puvis. Félix Vallotton, with his peculiar style and critical vision, was nonetheless a perfect adept of Puvis, as attested so well by the engraved portraits he made of him, the numerous figures and the layout of the painting Bathing on a Summer Evening (1892-93, Zurich, Kunsthaus), as well as by his landscapes treated in the classicizing manner, and his contemporary motifs {On the Beach, 1899, Switzerland, private collection). At the same time, about 1895, a second Neo-Impressionist movement was launched, stemming from the art of Paul Signac and then evolving into a simpler Divisionism, as shown in the exhibition at the Landesmuseum of Minister and the Musée de Grenoble in 1996-97. Signac, just like Cross, who was his neighbor on the Mediterranean coast, had an enormous influence everywhere, in France, in Holland, and in Germany thanks especially to Count Kessler around 1900, at a time when Cezanne's name was still practically unknown. His technique blended remarkably with the art of composition that he owed to Puvis and was already visible in In the Time of Harmony. That new language would contribute to increase the diffusion of Puvis's art in another direction, which would be confirmed in Matisse and his painting Luxe, calme et volupte (1905, Paris, Musée d'Orsay), in Derain and his composition appropriately titled The Golden Age (1905, Teheran, Museum of Modern Art), and in Jean Metzinger {Landscape, Sunset, 1907, Otterlo, Rijksmuseum Kroller-Miiller): Indeed in these works, the subject, forms and composition belonged to Puvis, while the color and treatment were Signac's. Paul Gauguin, Maternité au bord de la mer Musée de l’ Hermitage, Saint-Petersbourg Paul Cézanne, Le Repos des Baigneurs

1875-76, Merlon, The Barnes Fundation

Symbolism is the other great issue. It sprang up during the 1880s, and soon spread all over Europe, eventually becoming an authentic artistic movement that associated all forms of expression, from painting to poetry, sculpture and drama. Contrary to Naturalism and therefore anti-Impressionist, it sought to express philosophical reflections on life, death, the world or dreams, by means of images that assumed the form of symbols that were more or less explicit and played on correspondences. These reflections, often invested with mysticism and esoterism, opened onto highly subjective and sometimes hermetic visions, glorifying the weird, the fantastic or sheer dread. Symbolism cannot be boiled down to a tendency or a style: it blended very different strains, one of which was obviously animated by Paul Gauguin, and others by certain Nabis, who called themselves "initiates." For the most part, Symbolism's matrix was not Gustave Moreau, as has been repeated groundlessly, but above all without looking at the art of Puvis de Chavannes. Death and the Maidens, Hope, The Poor Fisherman, The Dream, Orpheus, The Sheperd's Song, like the large decorations such as Pleasant Land and The Sacred Wood, represent familiar myths or simple, fundamental allegories, which were so elaborated, that is, so totally devoid of naturalism, that they would serve as models for every generation of Symbolist painters, beginning with that of Odilon Redon, as has already been seen, up until 1914 and even later. Puvis de Chavannes's art constitutes the major fulcrum of European Symbolism around which that movement was arrayed. In France first of all, with the exception of Raphaël Collin who vulgarized his art, his disciples and pupils, Jean-Charles Cazin, Alexandre Séon, Alphonse Osbert and Henri Martin paraphrased it, transposed it or accentuated its features after the fashion of all mannerisms (Alphonse Osbert, The Mystery of the Night, 1897, Paris, private collection). Each of them would develop one particular aspect, starting from the landscape, the figure, classical or profane themes, such as Paul Chabas, Henri Le Sidaner, Emile-René Ménard. Edmond Aman-Jean, Seurat's fellow student and friend, whose art also appears to be close to that of Maurice Denis in its ideals, would dwell on compositions in which the decorative aspect prevailed {Girl with Peacock, 1895, Paris, Musée des Arts Decoratifs). The sculptors did not stay on the sidelines, for example Albert Bartholome, but the other sculptors preferred to stick to allegory, as had Puvis: that is the case of Antoine Bourdelle in the heroic genre or of Joseph Bernard in the graceful manner. Symbolism was even more widely diffused in Germany and Switzerland, since Impressionism had not found a fertile soil in those two countries. It was to develop there from Puvis de Chavannes, as well as from Arnold Bocklin himself. Both can, moreover, be connected in many respects: their art is often comparable and their evolution parallel, although Bocklin did not turn to mural painting. Hans van Marees, as been seen, was the first German painter to emulate Puvis de Chavannes. The founder of modern art in his country, together with Bocklin, he himself would exert considerable influence on Max Klinger, who was also under the sway of the Basel painter: but the work L'Heure bleue, painted in 1873 and undertaken when the artist was still in Paris, is a sure sign that Klinger had known how to look at Puvis. That is also the case of Franz von Stuck and even more so of Ludwig von Hofmann, whose entire oeuvre stems from Puvis {Idolino, c. 1892, Bielefeld, Kunsthalle), up to his mural compositions for Weimar. Hofmann, who would evolve in remarkable fashion toward a greater stylization, is a key figure given the influence he had on Expressionist painters such as Ernest-Ludwig Kirchner and Max Pechstein. In the 1890s, one of the prime movers in the Worpswede school, Heinrich Vogeler, borrowed Puvis's themes, converting them to a rather naive simplification. This clearly explains why so many elements in Paula Modersohn-Becker evoke Gauguin as much as the author of The Sacred Wood. Besides Hans von Marees, Puvis can be found in the early works of Max Beckmann, Franz Marc and Karl Hofer, the latter remaining loyal to the French master throughout his entire career {Three Bathing Youths, 1907, Winterthur, Kunstmuseum). But the great figure of Symbolism in that part of Europe is the Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler, who became equally famous in Germany. From the start, his ambition was to vie with Puvis, and he immediately became engaged in his field of predilection, that of mural painting {Architecture, Art of the Engineer, 1889-90, Zurich, private collection). In Paris, he exhibited works that Puvis saw and admired, like Night (1889-90, Bern, Kunstmuseum). By the subjects he tackled, in which he illustrated his vision of man and the universe, in his landscapes as in his simplest portraits, Hodler, like Gauguin, created a style that, while remaining loyal to Puvis, was one of the most original and promising developments of the future. Ferdinand Hodler, Night 1890 - Kunstmuseum Bern, Switzerland

At that time, Belgium was as close to Germany and Central Europe as it was to France. It represented, with the Groupe des XX in particular, an extremely important center for both literary and artistic Symbolism, owing to two personalities, the painter Fernand Khnopff and the sculptor George Minne. Having received his training from Xavier Mellery, who himself was under Puvis de Chavannes's influence, Khnopff is in fact the founder of Belgian Symbolism that would later nurture Surrealism. Khnopff looked directly at Puvis's works, as can be seen from Memories (1889, Brussels, Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts), with its frieze-like composition and the repetition of seven identical figures in front of a flat space formed by horizontal parallels. In turn, Khnopff would leave his mark on the Viennese Gustav Klimt, which would explain why the Beethoven frieze created for the Secession building in Vienna is so reminiscent of the French painter. Pierre Puvis de Chavannes - L’Eté, détail

1873 - Musée d’Orsay Fernand Knopff - Nu aux Fleurs Bruxelles, private collection

After Germany, it was in Scandinavia that Symbolism found its favorite ground, albeit in an exceedingly melancholy, pessimistic version, as can be imagined. Two different currents traverse it, opposed in their aesthetics, yet both under the sway of the art of Puvis, who appears to have so literally enthralled the artists of Norway, Sweden, Finland and Denmark that nearly all of them went to Paris to see the master's works, whose appeal might be compared to that of Raphael in Rome. One of these two strains put a particular emphasis on line, the accuracy of the contour at the expense of color and a careful composition: this is apparent in the paintings by Ejnar Nielsen, Magnus Enckell, Beda Stjernschantz, and Laurits Andersen Ring. Instead, Akseli Gallen-Kallela adopted a simpler draftsmanship, but much brighter colors. As for Vilhelm Hammershoi, it is obvious where his leitmotiv of the rear-view figure came from. His early linear style emulating classicism evolved into a slightly blurred contour, while he obsessively transposed into everyday life Puvis's neutral theatricality. The other Scandinavian current of Symbolism is entirely embodied in the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch, whose oeuvre is immense and whose posterity is impressive, especially in Central and Northern Europe. If we measure to what degree Munch was able to appropriate Puvis de Chavannes's contribution—and he would prove it all his life, in Puberty (1894-95, Oslo, Nasjonalgalleriet), which is the northern version of Hope; Bathing Men (1907, Helsinki, Ateneum) belonging to his Warnemiinde period, where we again have the motif of the ring behind a sequence of standing figures seen from the front, back or in profile; and in all his friezes bearing the tide Frieze of Life (1899-1900, Oslo, Nasjonalgalleriet)—we can just imagine the consequences of his legacy: This is the case of Mondrian whose Woods near Oele (1906, The Hague, Gemeentemuseum) comes straight from Munch's The Voice (1893, Oslo, Munch Museet), and whose approach cannot be understood without referring to Puvis. Munch created an entirely personal vision as did Gauguin and Hodler, in which the perfectly assimilated presence of Puvis continued nonetheless to play a role. Russia was to be at the same time an important center for Symbolism and for the diffusion of Puvis's aesthetic. A number of painters claimed to be more or less literal followers of the French master, among whom Viktor Borissov-Moussatov, Mikhail Nesterov, Nikolai Roerich and Kuz'ma Petrov-Vodkin. Leon Bakst's sets and costumes for the theater can be clearly observed in this context as well as Kasimir Malevich's first Symbolist works {Prayer-Study for a Fresco, 1907, Saint Petersburg, Russian State Museum), and those of Wassily Kandinsky, expressed, on the other hand, through the use of the Divisionist technique (Sunday. Old Russia, 1904, Rotterdam, Boijmans-Van Beuningen Museum). Every other country was influenced by Puvis to a certain extent: England, with William Rothenstein, Frederick Cayley Robinson and Augustus John; America, especially with John S. Sargent, who as a matter of fact would be commissioned to execute a decoration for the Boston Library after Puvis, Mary Cassatt, Maurice Prendergast, Arthur Glackens, Arthur B. Davies and Bryson Burroughs, his most conscientious disciple and a museum curator; while Greece would boast Constantinos Parthenis; and Portugal, Antonio Teixeiro-Carneiro. Edouard Munch - Mère et Fille, 1897 Oslo, Najonalgalleriet Spain was to be included with the special example of Catalonia that would become an authentic Puvis land, giving rise to Picasso. A School of Decoration was formed in Barcelona around Joaquin Torres-Garcia, who in turn discovered Puvis's work in 1907, and made it his ideal. Devoted to monumental art, it included artists such as Josep Obiols, Jaume Querol, Lluis Puig, Manel Cano, Tomas Aymat, and Josep Maria Marques-Puig. Torres-Garcia is the most singular example of Puvis's sway on an artist. The paintings and decorations he made before he left Barcelona represent a nearly identical, yet cruder, reappropriation, of Puvis's aesthetic. He would remain loyal to him throughout the 1920s, producing astonishing paintings imitating classical frescoes framed by architectural elements in wood, a key for understanding his later reliefs just before he discovered Mondrian's art in Paris, founded Cercle et Carre with Michel Scuphor, and went abstract. During the 1930s, he would once again show how devoted he was to Puvis, whom in fact he had not given up. After 1945. he still appealed to those fundamentals even in his most transposed allegories. Torres-Garcia and his circle are only one of the elements that Catalonia produced under the name of Noucentisme: but Joaquim Sunyer, the sculptors Manolo and Josep Clara and Julio Gonzalez when he was still a painter {Girls Sleeping on the Beach, 1914, Barcelona, Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya) are proof of Puvis's presence in that country. Symbolism spread throughout Europe and, in particular, as we have just seen, in a component that was essentially influenced by Puvis de Chavannes's art. Of course there were other factors involved, since the paths of creation are countless and formed by many crossings. This kind of discussion, appraisal and commentary demands endless nuances, or else it appears too elementary. The fact remains that the new trends of modern art that began to develop in the early twentieth century were steeped in this fundamental movement. Such was the context in which Picasso would embark on his career. Il reste que c'est imprégnées par ce mouvement de fond que les nouvelles tendances de l'art moderne ont commencé à se développer au début du XXe siècle. Il donne le contexte où s'énoncent les débuts de Picasso.

In 1900, Pablo Picasso appeared in Paris, a city taken up with the World Fair and steeped in Puvis's aesthetic. He saw Puvis's works exhibited at the Fair, and must have certainly gone to the Pantheon, the Hôtel de Ville, and the Sorbonne, in as much as hailing from Barcelona he was already familiar with everything Puvis's art represented: Hence, beginning in 1902, his paintings and drawings of the Blue Period with their cold color, like the blue of Sainte Geneviève Watching over Paris, their simplified, heightened forms, their lack of depth, their frontality and their very melancholy subjects. That sadness, the same as in Prodigal Son, permeates paintings like The Fisherman's Goodbye (1902, Japan, private collection), La Vie (Cleveland, The Cleveland Museum of Art), and The Tragedy (1903, Washington, National Gallery), whose titles speak for themselves. We should look at the Pink Period as a confirmation of the preceding one. Here Picasso went further in assimilating and transposing Puvis's contributions, in particular in the interpretation of space and the placing of figures within it. Acrobat on a Ball (1905, Moscow, Pushkin Museum) is certainly his masterpiece in this genre, with the succession of planes reduced to verticality and the sequence of figures, from the man seen from the rear with his accurate outline through the arabesque of the young acrobat on his ball to the distant horse. Picasso then proceeded to drastically simplify his images, which became veritable details—entirely revisited—of Puvis's compositions {The Two Brothers, 1906, Basel, Kunstsmuseum). Pablo Picasso - La Vie

1903 - The Cleveland Museum of Art Pablo Picasso - L’Acrobate à la Boule 1905 - Moscou, Musée Pouchkine That evolution, naturally associated with other factors, would lead him to Cubism. But we should point out that the composition of the Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907, New York, The Museum of Modern Art), its very format, its frontality, the layout of the vertical figures and even the crouching rear-view one, are right out of Puvis's world. Just prior to the birth of Analytic Cubism, Picasso again composed Large Nude by the Sea (1908-09, New York, The Museum of Modern Art), which features merely a standing figure holding, a drapery, seen in profile, one arm raised, painted in shades of pink and gray, standing out against a background of three horizontal parallels representing earth, sea and sky: did that bather not come straight out of Pleasant Land? Pierre Puvis de chavannes - La Charite,

1887 - Private collection Pablo Picasso - Femme et enfant au bord de la mer,1921. Circa 1850 - Chicago, The Art Institute Henri Matisse discovered or rallied the art of Puvis a bit later than Picasso. We have seen all that Luxe, calme et volupté (1905, Paris, Musée d'Orsay) owed to Signac, including the subject and the composition inspired by Puvis. Up until 1916, his presence would be felt. The subject of Le Bonheur de vivre (1905-06, Merion, The Barnes Foundation) is indeed that of a timeless pastoral scene, where in the center we see the motif of dancers in a ring, a reinterpretation of the group in the painting Death and the Maidens. Having parted with Fauvism, Matisse would come back to the expression of the line in his first version of Le Luxe (1907, Paris, Centre Georges-Pompidou, Musée National d'Art Moderne) whose layout and subject should be viewed as a transposition of Young Women by the Sea, an option the second version of that composition carried further {Le Luxe II, 1907, Copenhagen, Statens Museum for Kunst). The following year, the same appropriation of Puvis's themes, the subject and the form, together with a desire for the decorative, returned in Bathers with a Turtle (1908, St Louis, St Louis Art Museum) at the expense of radical simplification: a flat background formed by parallel bands of color, neither decoration nor detail, figures that are unrealistic since they are subject to the needs of the composition. In 1909-10, Matisse painted Music and Dance (Saint Petersburg, The Hermitage Museum), confirming his ear- Her achievements. Dance returns to the central motif of Le Bonheur de vivre, that now takes up the entire surface of the painting: the figures, reduced to a series of curves and counter-curves forming a loop, are inscribed in an abstract landscape consisting of just two strictly flat registers, painted in saturated color, green below, the other blue: Puvis's lesson, carried to its ultimate consequences. Later on, in 1916, Matisse was to come back to one of Puvis de Chavannes's favorite themes: the expression of rhythm by the succession of verticals in an oblong rectangular format, with the insertion of figures in a landscape enhanced by trees. At that time, Matisse painted Bathers by a River (Chicago, The Art Institute) where, in the monumental format of Puvis, sketchily rendered plant figures and motifs were directly placed side by side, enclosed in vertical registers, the ensemble producing a sense of extraordinary power but of masterful brutality as well. Andre Derain, one of the leading personalities of Fauvism, also took advantage of Puvis de Chavannes's oeuvre as well, offering his own interpretation of it in The Golden Age (1905, Teheran, Museum of Modern Art) with its self-explanatory title. The following year, Dance (1906, Amsterdam, Fridart Foundation) confirmed that direction in a wealth of decorativeness, while Bathers (1907, New York, The Museum of Modern Art) simplified radically and somewhat crudely one of the master's themes, presenting three schematic figures in an indistinct landscape, that is, forms giving rhythm to a pictorial surface. Maurice de Vlaminck, although reputedly so unpolished, did not ignore Puvis in his compositions, nor did Georges Rouault, Gustave Moreau's closest pupil, who took over Puvis's principles in Riders in the Twilight (1904, Zurich, Biirhle Foundation Collection). Picasso and Matisse of course are not the only ones. When one understands that Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia belonged to that same world, it is easier to interpret their later work. With its primitivist aspect borrowed from Emile Bernard, the painting The Bush by Marcel Duchamp (1911, Philadelphia, The Philadelphia Museum of Art) is a perfect expression of a Symbolist conception, as is Picabia's Adam and Eve (1911, Paris, private collection). Concurrently with Picasso, many other artists who were Cubist or who became so would display the influence they received from Puvis: such is the case of Albert Gleizes with Bathers (1912, Paris, Musée Municipal d'Art Modeme), Othon Friesz with Bathers of Andelys (1908, Geneva, Musée du Petit Palais), Henri Le Fauconnier with Abundance (1910, The Hague, Gemeentemuseum), Roger de La Fresnaye with Nude in a Landscape (1910, Paris, Centre Georges-Pompidou. Musée National d'Art Moderne), as well as Fernand Leger, whose painting Nudes in the Forest (1909-10, Otterlo, Rijksmuseum Kroller-Muller) with its oblong horizontal format and the profusion of off-keel cylinders in a twilight that makes an interpretation difficult, presents a solid orthogonal composition in which the figures and the perfectly integrated landscape express a great energy. Elsewhere, in Germany, as we have already seen, the Expressionist painters, those of the Briicke and the Blaue Reiter groups, especially Franz Marc, who were inspired by Ludwig von Hofmann and later by Hans von Marees in their creations would also adopt several aspects of Puvis, much like Max Beckmann did in his early days. Hans van Marées - Trois hommes dans un paysage

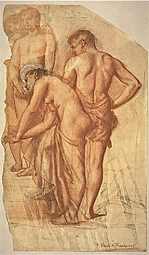

Düsseldorf, Museum Kunst Palast Study for Le Repos Circa 1865 - Musée d’Orsay, Paris In Belgium, Symbolism would continue to foment the first group of Laethem-Saint-Martin which before embracing Cubist manners a la Zadkine and joining up with Expressionism was to be largely nurtured by references to Puvis, as we can see in the works of Gustave Van de Woestyne, Leon and Gustave De Smet, Frits Van den Berghe, as well as in the very different ones of Albert Servaes.

After World War I the tone was to change, but there is no need to discuss the notion of a return to order here. In 1917, Picasso had already developed his so-called "Ingresque" style in the portraits he drew. In 1920, his paintings begin to reflect a new interest in construction and the assertion of volume which was far less "classicizing" or "Neoclassic" than entirely in the spirit of Puvis: in Women and Child by the Sea (1921, Chicago, The Art Institute), the arrangement of the figures inside a triangle, the profile presentation, the silhouette of the group standing out against a background of parallel horizontals, the color range and the absence of shading revisit the notions present in Antique Vision. The famous painting Three Women at the Spring (1921, New York, The Museum of Modern Art) entirely belongs to that manner, just like Seated Bather (1930, New York, The Museum of Modern Art), which returns to that same motif, this time monstrously distorted, set in front of the tripartite decor. Therefore Picasso was totally faithful to Puvis's ideal. Although with less assertiveness, Fernand Leger was too, illustrating in turn the theme of Dance (1929, Grenoble, Musée de Grenoble) in which he retained only two animated, hieratic figures. After Purism, Amédée Ozenfant found the humanist figuration again in allegories à la Puvis {The Bather's Grotto, 1930, Grenoble, Musée de Grenoble). At the time, Italy was not left behind, as the interest of a number of Novecento Italiano artists indicates. When they left behind the world of metaphysical painting, even Carlo Carra, and Mario Sironi, Massimo Campigli, and Mario Mafai in turn would follow Puvis's precepts, while the sculptor Arturo Martini would create The Fisherman's Wife (1930, Milan, private collection) which conforms in every aspect to the spirit of its model. In that context and at the crossroads of multiple influences, we have Balthus, close to De-rain and to the Surrealist universe {The Mountain, 1937, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art), or in another register, Robert Pougheon, whose compositions combine Menard's solutions with those of Andre Lhote {The Dioscuri, 1939, private collection). At the time, Puvis de Chavannes could continue to inspire Othon Friesz on the one hand, who openly referred to the French tradition, and on the other, Henri Matisse who, after his Nice period, rekindled his daring and returned to the theme of dance, and executed in 1930-31 a commission from Dr. Barnes, who asked him to decorate the premises of his founnances, essential silhouettes that become archetypes, abstract animals, timeless backgrounds. No effects, a sense of measure. Hence the overall impression produced by this painting: it is mute, silent. And essentially visual. Balthus - The Mountain 1937 - New York, Metropolitan Museum of art The means to achieve that result call upon structure and rhythm in the composition, and scrupulously comply with the two principal laws ruling the integration of painting in architecture: the law of the wall and of the frame. The wall will be emphasized by verticali-ty, meaning lack of depth, the distribution of its compartments either in parallel bands or three parts, and the rhythm created by the forms marking it. On that surface thus distributed, we then have forms that are simplified, barely modeled or used in flat tints, creating sequences, and united by the play of correspondences. There is an economy of colors and close-set values in order to avoid creating marked contrasts. The overall appearance, opaque and sometimes chalky, is similar to that of frescoes; it is obtained by using a dry material, with scarcely any binder, and a broad, at times thick, brushstroke that may give the impression of having been scraped, even in the small formats. The law of the frame that essentially concerns monumental painting was respected to the letter by Puvis who, in his compositions, took into consideration the situation of the painting in space and in its location: an oblong strip, a vertical surface, a triptych, a door frame, a tympanum, and solutions adapted to each configuration. Often they were all the more appropriately selected from a repertory that Puvis gradually amassed, as Rodin was to do, and were improved on and used over and over according to his needs: thus the motif formed by the central figure of the seated woman with her child in Summer (1873, Paris, Musée d'Orsay). Lastly, the rear-view figures that appear throughout the work like a leitmotiv, the theme of the dance, the flying forms of The Dream, The Sacred Wood of Lyon, the Muses of Boston, the layouts of Hope and The Poor Fisherman, The Prodigal Son and The Toilette (1883, Paris, Muse d'Orsay) are just so many images or motifs of sheer creation that have been rendered unforgettable and express one of the highest degrees of the art of painting. From 1880 on, Puvis de Chavannes dominated his age, and his ascendancy produced Raphael Collin as well as Paul Gauguin, and the utterly different visions of Seurat and Munch, Bourdelle and Maillol. Furthermore, it allows for a profound understanding of the works of Picasso and Matisse and, through their differences, that which unites them. His influence did not just effect the field of painting and sculpture, but touched also on the decorative arts and in particular the art of stained glass, as it was pranced by Art Nouveau glassmakers like Emile Galle. In the applied arts, especially in posters, he served as a model for the creations of Eugene Grasset and Carlos Schwabe, as well as the illustrations of Henri Rivière. His aesthetic left its mark on countless photographers, particularly in the period of Pictorialism, as we can see in the pictures by Heinrich Kiihn, Clarence White and Gertrude Kasebier. In drama, when Symbolism countered Realism, scenography borrowed all its characteristics from Puvis’s art; first of all in the Théâtre d'Art directed by Paul Fort, and later by Lugné-Poe, whose childhood friends had been Sérusier, Maurice Denis, Gauguin and Vuillard in particular. His influence can also be detected in the early cinema: the first great French cinéma director and theoretic, Louis Feuillade, wrote in La Série esthétique in 1910 a manifesto for "film authors" in which he proposed "the art of painting" as an example, citing that of Puvis in particular. Puvis de Chavannes also left his mark on those composers with whom he was associated and whom he inspired, such as Ernest Chausson, Claude Debussy and especially Erik Satie. Many writers admired him, including Emile Zola, Joris-Karl Huys-mans, Alfred Jarry and Catulle Mendes, and honoring him along with the hundred poets of the Album des Poêtes that Rodin solemnly offered him on the occasion of the banquet, were Emile Verhaeren, Rémy de Gourmont, Georges Rodenbach, Henri de Régnier, Jean Richepin, José-Maria de Hérédia, Paul Verlaine, Paul Fort and Stéphane Mallarmé. Puvis de Chavannes domine son époque à partir de 1880 et c'est le résultat de son magistère qui produit aussi bien Raphaël Collin que Paul Gauguin et les visions si différentes de Seurat ou de Munch, de Bourdelle ou de Maillol. Par-delà, il permet de comprendre de façon profonde les créations de Picasso et de Matisse et ce qui, à travers leurs différences, les rapproche. Son influence ne se marque pas seulement dans le domaine de la peinture et de la sculpture, mais touche aussi celui des arts décoratifs et en particulier l'art du vitrail, tel que l'ont pratiqué les verriers de l'art nouveau comme Emile Galle. Dans les arts appliqués, notamment dans le domaine de l'affiche, il a servi de modèle aux créations d'Eugène Grasset et de Carlos Schwabe, comme dans celui de l'illustration, à celles d'Henri Rivière. De nombreux photographes ont été marqués par son esthétique, en particulier à l'époque du pictorialisme, ce que montrent les clichés de Heinrich Kûhn, de Clarence White et de Gertrude Kàsebier. Au théâtre, quand le symbolisme a réagi contre le réalisme, la pratique scénique a emprunté toutes ses caractéristiques à l'art de Puvis, tout d'abord au Théâtre d'art dirigé par Paul Fort et à sa suite par Lugné-Poe, qui fut l'ami de jeunesse de Sérusier, de Denis, de Gauguin et de Vuillard notamment. Cette influence se manifeste aussi dans le cinéma dès son origine : le premier grand réalisateur et théoricien du cinéma français, Louis Feuillade, écrit en 1910 dans La Série esthétique un manifeste qu'il adresse aux « auteurs de films » et où il leur propose comme paradigme « l'art du peintre » et singulièrement celui de Puvis. Les compositeurs avec lesquels il a entretenu des liens et qu'il inspirait, tels qu'Ernest Chausson, Claude Debussy et surtout Erik Satie seront tout autant marqués par son art. De nombreux écrivains l'ont admiré, d'Emile Zola à Joris-Karl Huysmans, d'Alfred Jarry à Catulle Mendès et lui ont rendu hommage tels les cent poètes de l'Album des poètes donné solennellement par Rodin au peintre lors du banquet, ainsi Emile Verhaeren, Rémy de Gourmont, Georges Rodenbach, Henri de Régnier, Jean Richepin, José-Maria de Hérédia, Paul Verlaine, Paul Fort ou encore Stéphane Mallarmé.

What artist, since the sixteenth century and by the sole means of his art, has received such recognition, especially from other artists, and exerted such a supremacy in his lifetime, one that later influenced so many and so different generations? Puvis de Chavannes created—even if the word may be meaningless for some—a universal art that commanded admiration by its simplicity and harmony. Composition, expressiveness of forms and colors and subject were so thoroughly blended that their effect was immediate and then became eternal. Puvis's clear and comprehensible work offers models that can be reproduced, assimilated, transposed and combined: one need only keep a structure, a group of forms, a line, a color combination, a part, a detail, an ensemble, an image. Starting from there, each was able to make his own way. Puvis de Chavannes is an artist who embraced a tradition that he was able to keep alive, built his own vision and paved the way for the future. How can we even conceive of a break that can be neither described nor situated, when we can observe, on the other hand, an authentic continuity in the history of art between the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries that Puvis's art and posterity insured. Does not such a natural sequence, such a continuous transition, once again offer an illustration of the life of forms and the proof that history has not come to an end?

Henri Matisse - Nu bleu II 1952 - Paris, Musée National d’Art Moderne

|

|||