|

|||

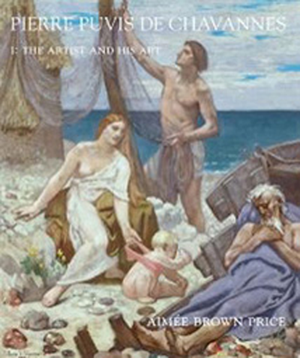

| The Art Gallery Pierre Puvis de Chavannes

In 1976, a retrospective exhibition on the work of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes was held at the Grand Palais in Paris, before traveling to the Ottawa National Gallery. The catalogue extended beyond the scope of the Lyonnais artist’s easel paintings to include his decorative output, for in addition to being France’s leading mural painter in both public and private domains, he received prominent commissions in the United States such as the still intact grand staircase of the Boston Public Library. The rediscovery of Puvis de Chavannes was a tour-de-force led by Louise d’Argencourt and Jacques Foucart, and yet it underscored the lack of a detailed catalogue comprising the artist’s vast and habitual output of studies, variations, reworkings and adaptations. The more compact exhibition that took place in1994 at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam further intensified the need for a reference catalogue. The past decade has seen a surge of interest in Puvis de Chavannes. As a result of several major sales, such as the auction of nearly seventy works on 10 December 2003 – where the Musée d’Orsay acquired a small and unusual panel painting entitled Vue du château de Versailles et de l’Orangerie made in 1871 during the Paris Commune when the artist was in exile with his family (see update 11/12/03) – and the entry of several important paintings in public collections – e.g. the 2001 acquisition by the Musée des Beaux-Arts d’Angers of the painting from 1853 entitled Mademoiselle de Sombreuil buvant un verre de sang pour sauver son père (cat. n° 29); the 2009 acquisition by the Musée d’Orsay of an early work (whose title Négrillon à l’épée (cat. n° 8) remains to be clarified by future research) that entered the museum a year after Orphée1, formerly in the possession of Judith Gautier (cat. n° 295) and figuring in the Catalogue Raisonné under the name of its previous owner. These sales and acquisitions further heightened the need for a comprehensive study. Aimée Brown Price, in her two-volume Pierre Puvis de Chavannes recently published by Yale University Press, undertakes this arduous research, although she mainly focuses on the painted works. The first volume of the study provides a biography and stylistic analysis of the oeuvre, and features some very interesting appendices that refer to the acts of the notary who, on 14 November 1898, was entrusted with drawing up the artist’s death inventory for the atelier on 11 Rue Pigalle and the Neuilly estate. The chronological biography is highly annotated and superbly illustrated. It suggests various insightful comparisons, situating Puvis within his era and highlighting his originality, and reviews the critical reception of his work, although some might have reservations about the overly flattering slant of the selected excerpts and the rather biased analysis of certain events. The inclusion of some of the caricatures that Puvis delighted in sketching throughout his life adds a new unconventional note to the biography of an artist who has been too often relegated among the humorless rigorists. The bibliography that concludes the first volume is divided into “primary sources” for documents and archives, and “secondary sources” for strictly bibliographical material. Among the primary sources, there is a conspicuous distinction between documents belonging to private owners and those belonging to public institutions. Such methodology does not seem to apply to the so-called secondary category, which liberally blends general overviews that merely mention Puvis by name without any critical commentary and which barely reappear in the second volume, together with cutting-edge articles that oddly figure in the entries but not in the bibliography, with the exception of some past and present writers such as Théophile Gautier, Léonce Bénédite, André Michel and Aimée Brown Price. Why, for instance, neglect Henri Dorra’s anthology Symbolist Art Theories: A Critical Anthology [2] which does not merely cite Gautier’s public criticism in 1861 but probes the connections between writer, artist, subject matter and intent, at the time when Puvis was presenting his decorative panels Concordia and Bellum at the Salon Officiel, for the Musée d’Amiens? Following the appendices, there is a surprising absence of indexes, which would have not been so difficult to include. Why is there no index of collectors or no index of locations which, beyond a dry enumeration, would have shed light on the history of tastes and collections? It is also surprising that in this lengthy list, there is no reference to the impressive Bulletin that the Comité Puvis de Chavannes has been publishing for several years now. Some of their articles and notes might have enhanced the catalogue (for instance by enabling identification of the Portrait de femme (cat. n° 24) as the painter’s sister Madame de Vaugelas, or by expounding on the sketch Virgile catalogued under n° 409). Some of the “updates” that conclude the Bulletin seem to have escaped the notice of the person who compiled the captions for the works listed in the second volume, which we shall now discuss. Modestly titled A Catalogue Raisonné of the Painted Work, the second volume – which for some reason comprises several large sketches in chalk, pencil and brown ink wash on canvas, while omitting others – such as reference n° 86f which belongs to a Parisian collection –, far surpasses a commented enumeration of Puvis de Chavannes’ works, for it provides detailed documentation of texts and images, although some of the choices are baffling. As of the first entry on the Trois personnages in the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk (ill.), one realizes that the brevity of the “Sources and Literature” section is due to the numerous notes that cross-refer to the Bibliography in the first volume…as well as to the List of Exhibitions at the end of the volume in hand. Another awkward crisscross between the two volumes: the full-page color images in the first volume only appear as black and white plates in the second volume. There is never any indication of a page number following a name or location matched with a date; this will not ease the task of future researchers who, unless they systematically return to the source, will be forced to fumble about. Modestly titled A Catalogue Raisonné of the Painted Work, the second volume – which for some reason comprises several large sketches in chalk, pencil and brown ink wash on canvas, while omitting others – such as reference n° 86f which belongs to a Parisian collection –, far surpasses a commented enumeration of Puvis de Chavannes’ works, for it provides detailed documentation of texts and images, although some of the choices are baffling. As of the first entry on the Trois personnages in the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk (ill.), one realizes that the brevity of the “Sources and Literature” section is due to the numerous notes that cross-refer to the Bibliography in the first volume…as well as to the List of Exhibitions at the end of the volume in hand. Another awkward crisscross between the two volumes: the full-page color images in the first volume only appear as black and white plates in the second volume. There is never any indication of a page number following a name or location matched with a date; this will not ease the task of future researchers who, unless they systematically return to the source, will be forced to fumble about. The inclusion of related works is always enlightening in this sort of anthology, but it would have been more effective with more clarity of purpose in the choice of reproductions, and with an availability of bibliographical references. Alluding again to Puvis’ earliest work, what is the point of showing a drawing that doesn’t depict any of the figures in the Trois personages, and what do art historians say about it? If it doesn’t come with a date, and might just as well be an original as a copy, why is it present? And, still bearing the researcher in mind, couldn’t the caption for this drawing have been supplemented with a more informative reference? Why doesn’t it say “Boucher (1874)” – which appears in the general bibliography – and thereby indicate, even minimally, the dissertation presented by Marie-Christine Boucher in 1974 on the ensemble of Puvis de Chavannes’s works conserved in Paris at the Musée du Petit Palais. The reproduction displayed under n° 362a, which does not cite any current location or technical information, corresponds to a large 34x24.5cm page, which has been frequently exhibited over the past few years. It now belongs to the Musée de Beauvais (Oise), having been donated in 1997 by Marie-Thérèse Laurenge who had bought it ten years beforehand at the Galerie Coligny [3]. While the entries for each number draw abundantly on the 1976/77 catalogue, they sometimes make stimulating comparisons and launch new paths, although the visual connection between certain works awaits future confirmation. The influence of Henry Scheffer on the young Puvis de Chavannes, mentioned several times, is interesting but does not seem totally convincing. The comparison is merely demonstrated with black and white plates (cat. n° 13 et n° 13a), where the composition and identical poses of the similarly-aged figures does not compellingly link two techniques that seem quite different, which is to be expected when juxtaposing an intimate and roughly painted portrait with an official portrait intended for public display. The exhibitions at the Palazzo Grassi (Venice) in 2002 and at the Musée de Picardie (Amiens) in 2005 both aimed, although with very different means, to revise Puvis’ overall career in light of his contemporaries and subsequent artists, and yet some parallels were only hinted at while other were overemphasized. The time is thus ripe, equipped with Aimée Brown Price’s Catalogue Raisonné, to envisage a new monographic event on Pierre Puvis de Chavannes – in which his passion for the pastel medium should not be disregarded – so as to illuminate the gray areas that eclipse the man and his oeuvre. In the meanwhile, and despite the many reservations elicited by Aimée Brown Price’s choices and by Yale University Press’s layout, researchers now have at their disposal a perfectible work tool that nevertheless offers a vast repertory of images and references. It is to be hoped that readers will freely add annotations, and thus transform the book into an ideal working instrument long-awaited by researchers and dreamed of by Puvis’ admirers so as to erect, upon this bedrock, a rightful monument to the “hero” of generations of artists. Aimée Brown Price, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. Volume I: The Artist and his Art. Volume II: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Painted Work. New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2010, 450 pp, $250. ISBN 9780300115710. Dominique Lobstein, Thursday 15 July 2010 Notes [1] Both paintings will soon be featured in an update on recent acquisitions of the Musée d’Orsay. [2] London, University of California Press, 1994, pp 35+. [3] Josette Galiègue, chief editor, De l’école de la nature au rêve symboliste, Paris, Somogy, 2004, p. 203. Translation : Nathalie Lithwick Aimée Brown Price, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. I. The Artist and his Art, II. A Catalogue Raisonné of the Painted Work, New Haven et Londres : Yale University Press, 2010, 260 et 485 p. in 4°, très nombreuses ill. noir et coul. Ces deux imposants volumes sont l’aboutissement d’une carrière entièrement consacrée à l’artiste dont l’auteur eut la révélation en regardant, dans sa jeunesse, une méchante reproduction du Pauvre pêcheur et dont l’œuvre fit l’objet de sa thèse soutenue en 1972. Le catalogue était attendu depuis plus de vingt ans, mais on sait quelle patience exige une telle entreprise. Dans l’introduction du premier volume, Aimée Brown Price juge nécessaire de rappeler l’utilité des catalogues ainsi que des monographies face au mépris dont les couvre une certaine histoire universitaire de l’art. Qu’elle se rassure : bien que work in progress comme tout catalogue raisonné, le sien restera encore longtemps fondamental quand les ouvrages auxquels certains universitaires doivent aujourd’hui une éphémère célébrité seront tombés dans un juste oubli. Le premier volume comprend une monographie richement illustrée suivie en annexe de documents notariaux (dont l’inventaire après décès), une longue bibliographie précédée de la liste des sources (archives publiques et privées) et un index. La présentation en serait irréprochable si l’on ne constatait pas un nombre important de coquilles ou de lapsus : Augone pour Ausone (p. 90), Lavigne pour Lavagne (p. 197, n. 56), Lemeire pour Lameire (p. 201, n. 180), « Le thème de la décoration [ !] de Saint-Jean Baptiste » (p. 230). Élie Delaunay aurait été (p. 92) l’auteur d’une peinture murale au Panthéon en … 1869 ! À cela s’ajoutent des oublis dans l’index (pour Falguière, il manque la note 12, p. 176). D’un éditeur comme les presses de l’Université de Yale, on attendrait un peu plus de soin dans la relecture du manuscrit. La bibliographie est conçue, selon le regrettable usage actuel, par ordre alphabétique d’auteurs, ce qui permet de mentionner les ouvrages en abrégé dans les notes (et oblige ainsi le lecteur à un perpétuel va-et-vient), mais ne facilite pas les recherches complémentaires. L’auteur néglige un certain nombre de publications récentes, soit qu’elle les indique dans sa bibliographie sans les avoir utilisées dans son étude ou qu’elle les ignore purement et simplement : ainsi ne trouve-t-on ni le catalogue de l’exposition Le temps de la peinture. Lyon 1800-1914 (Lyon, 2007), ni celui de l’exposition Puvis de Chavannes au Musée des beaux-arts de Lyon (ibid., 1998). Ces lacunes laissent la fâcheuse impression que l’auteur, devant l’ampleur de la tâche, a fini par renoncer à tenir à jour sa documentation. La monographie est conçue selon un plan chronologique par décennies : « The 50s », « The 60s », …. Outre son arbitraire, ce découpage conduit à des répétitions et surtout à la fragmentation de certaines questions, comme l’esthétique murale de Puvis ou la réception de ses oeuvres, qu’il eût mieux valu traiter dans la durée, ne serait-ce que pour faire apparaître plus clairement les évolutions. L’auteur (et c’est sans doute le principal mérite de ce premier volume) se fonde largement sur la correspondance du peintre, dont seule une petite partie fut publiée dans les années qui suivirent sa mort. Aussi doit-on regretter qu’une édition critique de toutes les lettres conservées, la plupart en des mains privées, n’ait pas encore été entreprise, regret d’autant plus fort que les passages inédits qu’Aimée Brown Price reproduit dans les notes (ils sont traduits en anglais dans le cours du texte) sont émaillés de fautes de lecture dont certaines sautent aux yeux : « rétorqués » pour « retoqués » (p. 198, n. 95), « gradin » pour « gredin » (p. 204, n. 14), « les parisiennes sont fermées partout » pour « les persiennes… » (p. 214, n. 356), etc…, mais dont d’autres peuvent dénaturer le sens du texte à l’insu du lecteur. La connaissance que l’auteur a de cette correspondance lui permet d’apporter des éléments nouveaux sur des points particuliers tels que la commande, refusée par le peintre, pour la Bourse de Bordeaux (p. 90-91), mais aussi et surtout sur son existence et sa personnalité. Ainsi son idylle avec Berthe Morisot occupe-t-elle de nombreuses pages, ce qui peut sembler excessif au lecteur jusqu’à cette lettre dans laquelle Puvis évoque son « fantôme en peignoir blanc », ce qui appellerait quelques précisions (p. 197, n. 75). Certaines lettres dans lesquelles il s’exprime sur la situation politique ou sur l’état de l’art sont d’une violence qui jure avec l’image qu’on se fait d’ordinaire du personnage. Ses rapports avec l’Académie des Beaux-Arts furent plus complexes et moins conflictuels qu’on a l’habitude de le dire (bien que l’auteur affirme (p.102), sans indiquer de source, que des notables de l’Institut auraient essayé d’empêcher l’achat par l’État du Pauvre pêcheur) : en réalité, Puvis aurait nourri l’ambition d’y entrer, mais il explique dans une lettre à Falguière qu’il fut empêché de poser sa candidature en raison de la dispersion de ses œuvres qui empêchait de prendre une vue exacte de sa carrière (p. 176, n. 12). Aimée Brown Price omet cependant de rappeler que Puvis figura plusieurs fois sur la liste des artistes élus par les membres de l’Académie des Beaux-Arts parmi lesquels étaient tirés au sort les jurés adjoints du prix de Rome, ce qui constituait en fait une incitation à se porter candidat. Cette omission est symptomatique d’une ignorance des institutions difficilement compréhensible chez la spécialiste d’un peintre comme Puvis. Qu’elle date (p. 130) la Triennale de 1885 n’est peut-être qu’un lapsus, mais on lit un peu plus haut que l’Académie nationale des Artistes français projetée par Chennevières aurait été « a progressive rival of the Académie des Beaux-Arts » et qu’elle fut créée en 1875. Parmi bien d’autres erreurs, on est surpris de lire (p. 99) que Jules Ferry était « Directeur des Beaux-Arts et Instruction Publique » et (p. 108) que Chennevières était encore directeur des Beaux-Arts en 1889 : Castagnary aurait-il apprécié cette confusion ? Parmi les problèmes iconographiques et stylistiques posés par les œuvres, l’auteur souligne avec justesse l’opposition, autour de 1880, entre les thèmes traités dans les grands décors et ceux qui dominent dans les tableaux – la solitude, la mélancolie – dans lesquels elle voit le reflet d’une grave crise intérieure. Elle traite longuement de l’esthétique murale et des valeurs décoratives, fondement de l’art de Puvis. Son parallèle entre ses compositions murales et l’architecture de Labrouste (p. 108) peut par contre laisser dubitatif. Quant au long développement qu’elle consacre au classicisme (p. 38 sqq.), il n’est pas certain qu’il éclaire bien celui de Puvis dans la mesure où s’y mêlent les humanités sur lesquelles se fondait l’éducation scolaire, l’impassibilité de la statuaire antique selon Winckelmann et la poésie de Leconte de Lisle, l’art pour l’art et la peinture néo-grecque, les Églogues de Virgile et le trait de redessiné de Couture, …. Le catalogue des peintures qui occupe le second volume constitue évidemment l’apport essentiel de l’ouvrage, à la fois par la masse d’informations contenue dans les notices et par les œuvres restées inédites ou inconnues – auxquelles il faut ajouter celles qui ne sont plus connues que par une ancienne photographie. La plupart d’entre elles sont relativement mineures : portraits de jeunesse, petits paysages, esquisses de grandes compositions ; mais elles enrichissent et nuancent considérablement notre connaissance de l’art de Puvis, surtout à ses débuts. À cela s’ajoutent les très nombreuses reproductions de dessins de sa main ainsi que d’œuvres contemporaines ou anciennes qui permettent de mieux comprendre son travail, même si la pertinence de quelques comparaisons reste problématique. Le catalogue s’achève par les listes d’œuvres détruites et d’œuvres dont la trace est perdue, puis par les œuvres douteuses (« Paintings for further study », FS 1-17), et les nombreuses attributions erronées, copies et pastiches (A 1-177). Malgré une origine prestigieuse, la Femme nue cataloguée comme authentique (n° 159) aurait plutôt sa place en FS, sinon en A ; inversement, la Scène orientale et la Bacchanale n° FS 2 et FS 1, exposées à Lyon en 2007 (n° 210 et 211) semblent bien de la main de l’artiste. Rappelons que la Scène mythologique (A 77) passée en vente chez Sotheby en 1967, est en fait une œuvre du peintre Paul Milliet, un élève de Gleyre plus connu, du moins des historiens de l’art antique, par le recueil qui porte son nom. Pierre Vaisse | |||